Introduction

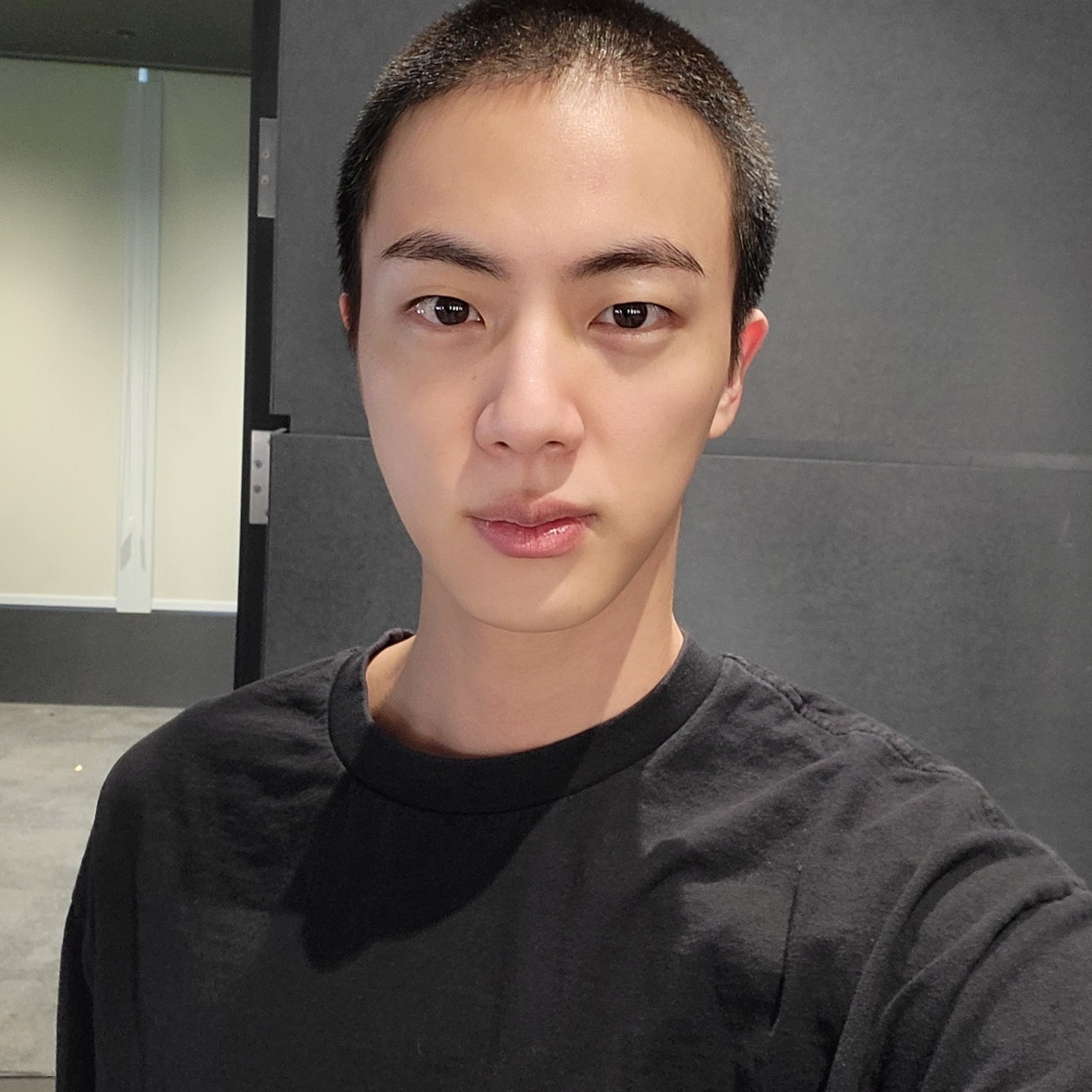

On a snowy day in December of last year, Jin, the oldest member of BTS, entered his assigned military boot camp, located close to the border between the two Koreas. Two days before his enlistment, he uploaded a picture of his military buzz cut—a requirement for all enlistees—to Weverse, a platform that connects BTS to their global fanbase, ARMY. The photo launched a frenzy of discourse on the internet: Twitter mutuals and fellow ARMY of mine weighed in on the issue, lamenting the reality of having to wait until 2025 for all of the members to complete their military service. With Jin’s departure, much of the world became aware of South Korea’s policy of universal male conscription for the first time.

Jin's haircut, uploaded to Weverse.

Jin's haircut, uploaded to Weverse.South Korea not only mandates military service of at least 18 months for all cis, able-bodied men ages 18 to 35,1 but is also one of the few remaining countries whose high courts do not acknowledge the right of conscientious objection—the government has sent more than 10,000 conscientious objectors to prison since 2000.2 Failing to fulfill one’s military duty is highly stigmatized and scorned upon by the rest of society.3

Jin’s enlistment—and BTS’s official announcement of their intention to serve in October of last year—came after years of debate among politicians and Korean citizens regarding who should be exempted from what is commonly framed as the “passport to male adult life in Korean society.”4 As of now, South Korean law gives special exemptions to high-performing athletes and classical musicians and dancers if they have won top prizes of international prestige. Yet, K-pop stars and other entertainers (e.g. rappers, actors) are not given such benefits, and high-profile individuals are regularly accused of evading the draft.5

Following BTS’s announcement to enlist in October of last year, media outlets, politicians, and social media users all praised the group’s willingness to serve the nation. In its official press release, Big Hit Music, BTS’s parent company, announced that in “respect[ing] the needs of the country,” it was necessary for “these healthy young men to serve with their countrymen.”6 Yet, what does this language surrounding national duty say about the ties between military service and masculinity? What do public reactions to those forgoing or dodging the draft say about who is considered “man” enough? How did the draft come to be an inescapable and inevitable part of Korean male adulthood? The structures we take for granted were intentionally created to serve a specific purpose, oftentimes more recently than we may think.

While so many BTS fans were quick to express their sadness and outrage over their favorite idols being sent to the army, I noticed that there was little criticism of the process of enlistment as a whole—of the realities that make military service in South Korea mandatory for men in the first place. The only critical reading of South Korea’s draft in relation to BTS that reached a wide audience was by Nodutdol, a leftist Korean diasporic organization, which published a thread7 on the history behind mandatory military service and its ties to U.S. imperialism.

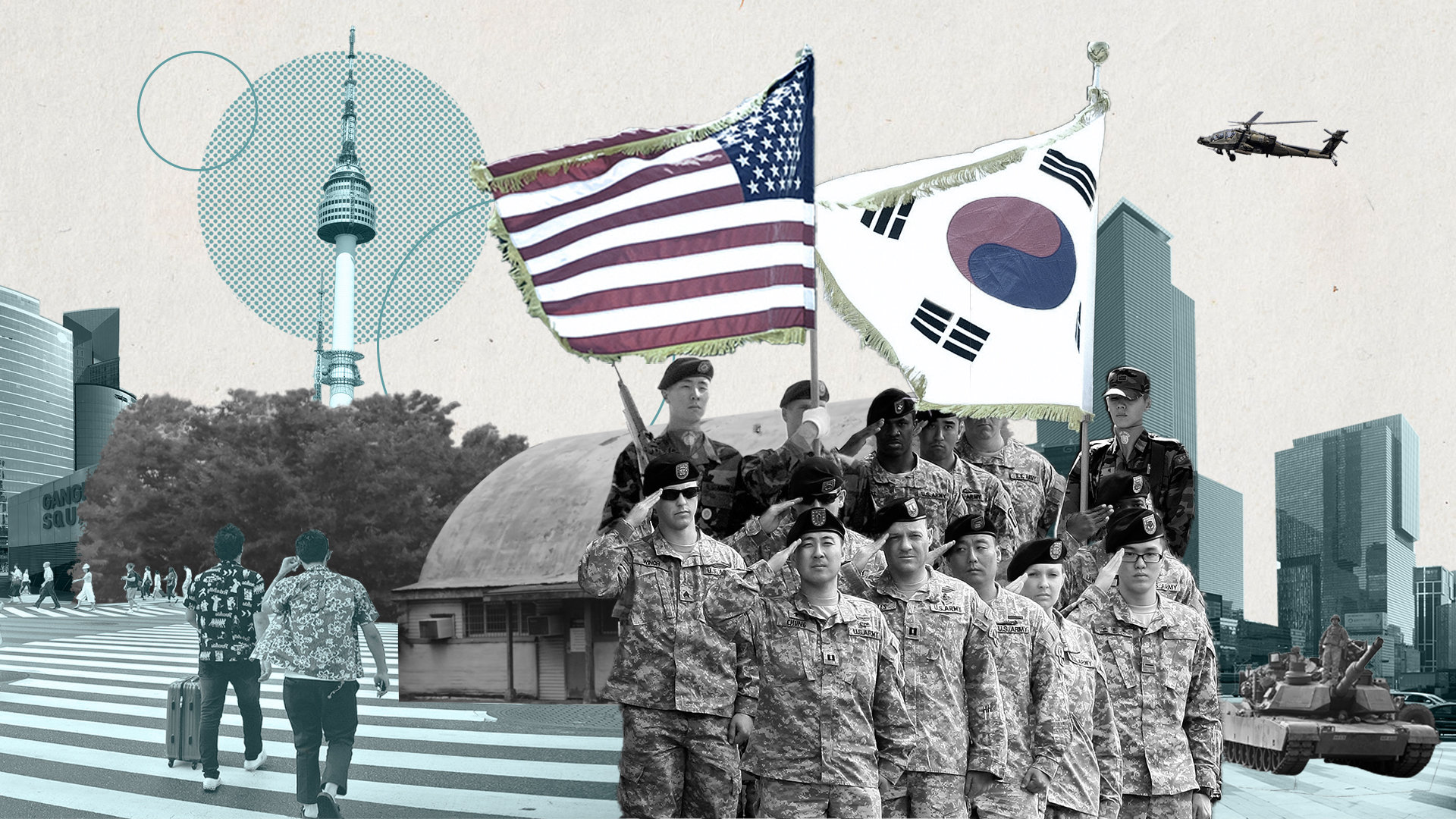

BTS is fulfilling their national duty—but is this really something to celebrate?

BTS and the military. Graphic from Kate Sammer at CNBC

BTS and the military. Graphic from Kate Sammer at CNBCA brief history of militarism in Korea

To understand and critique the realities of universal male conscription in Korea, it is first necessary to examine the following circumstances faced by South Korea: national division, the Korean War, prolonged military confrontation, and fervent anticommunism.8 Following 35 years of colonialism under the Japanese Empire, the South Korean state was established in 1948 by the U.S. military-backed, conservative landed class, while North Korea was supported by the Soviet Union. By then, tens of thousands of U.S. servicemen had already arrived on the southern half of the peninsula. From 1950 to 1953, the North and South fought in what was essentially a proxy war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, marking the height of the Cold War. The Korean War solidified the nation’s division at the 38th parallel, an arbitrary line that was drawn by two U.S. military officers. While the war ended in an armistice agreement between the United Nations (a proxy for the U.S.), North Korea, and China, without any formal peace treaty, the two Koreas are technically still at war.

In the years of state-building following the Korean War, anti-communist ideology—espoused by the U.S. military and conservative Korean elite —formed the bedrock of national identity in the South. A military regime that would protect citizens against the threats posed by the communist North was considered necessary for national security. Thus, mandatory military service for all men was implemented in 1957, during the early years of South Korea’s path to modernity.

Military violence thus made possible the conditions for all subsequent creations of Korean sociopolitical life. Scholar Seongsook Moon calls this “militarized modernity.” Militarized modernity, a sociopolitical and economic formation that emerged in South Korea during the decades following the Korean War, denotes a trend of modernity characterized by the fusion of disciplinary power and pervasive force. In the case of South Korea, the pursuit of modernity included the anticommunist state’s attempt to remold its population into “useful members of the body politic through the combined use of discipline and physical violence.”9 This “remolding” was most clearly seen through the mobilization of manpower through universal male military conscription, a practice that is also seen in the North (and to a much more intense degree).10 Thus, a lasting repercussion of Korea’s continued division is active militaries on both sides of the DMZ. Notably, the U.S. commander has full wartime control over South Korea’s military.11

Photo taken by Jung Yeon-je for Getty Images.

Photo taken by Jung Yeon-je for Getty Images.Problems within the military today

Today, many South Korean young men no longer resonate with the belief that it is a man’s national duty to counter communism by enlisting.12 Yet, mandatory military service remains deeply ingrained in Korean notions of masculinity and national identity. Many people still believe that universal male conscription is an equalizer of sorts—men of all socioeconomic backgrounds are required to serve for the same amount of time. This is a myth of fairness. As Moon argues, there are abundant examples of military service corruption among the wealthy and powerful in South Korea.13 Supplemental, or non-active service, is perceived as a less onerous route to fulfilling military service and is common among sons of upper-class families who use their money and connections to avoid active military service. Furthermore, college education has historically functioned as a path to deferring the draft, leading to more class-based equity problems when it comes to universal conscription.14 Those who advocated for BTS’s enlistment claim that it is a duty that is expected of all Korean men—yet, it is clear that enlistment was never a truly standardized practice to begin with.

For celebrities, especially, one’s completion of mandatory military service demonstrates the achievement of a specific, patriotic ideal of manhood. In her piece “The good, the bad, and the forgiven: The media spectacle of South Korean male celebrities’ compulsory military service,” scholar Yezi Yeo discusses the social meanings behind male conscription through the lens of high-profile celebrity cases, claiming that “these media scandals reinforce what it means to be a true ‘Korean man.’”15 From the notorious case of Seungjun Yoo, who gave up his Korean nationality in order to free himself from conscription, which led to the government banning Yoo’s entry to South Korea indefinitely, to the controversy surrounding global star Psy’s alleged “undutiful” military service performance and his decision to enlist twice in order to boost his public image, it is clear that both South Korean manhood and citizenship are sanctified by the sacred duty to serve.16 Perceptions of this sacred duty relies on gendered assumptions about who (cis men) is to protect whom (women: mothers, lovers, etc.) and against whom (the communist North).17

In maintaining these strict gender-based policies, the South Korean military regime further marginalizes populations that do not conform to the system’s rigid ideas and assumptions about manhood. In order to maintain a “cult of tough and aggressive masculinity,” conscripts are constantly subjected to disciplinary abuse designed to inculcate a masculinity characterized by toughness, aggression, and obedience.18 The South Korean military culture is notorious for being strict, and at times, violent: in 2014, a conscript was beaten to death by higher-ranking officials.19 In a country that does not legally accept same-sex partnerships, the military regime is particularly abusive towards LGBTQ+ individuals. Under military law, LGBTQ+ soldiers are banned from same-sex relations and can face up to two years in prison if caught. Transgender soldiers are banned from serving: in 2021, the defense ministry declared gender affirming surgery a mental or physical handicap.20 The oppressive rigidity of the system and the clear gender bifurcation arising from universal male conscription should prompt us to question the legitimacy of the military in the first place.

Image designed by Crystal Tai for the Wall Street Journal.

Image designed by Crystal Tai for the Wall Street Journal.Conclusion

Whose interests does universal male conscription serve, and what history does this practice carry with it? These are just a few of the questions we must begin to ask when thinking critically about the draft and the power wielded by outside forces in Korea.21 Militarized masculinity is a concept not only relevant to conscription: it has far-reaching effects in Korean society. The consequences of the gender bifurcation resulting from a universal male draft—and claims of the draft promoting anti-male discrimination—can be seen everywhere, from the rise of misogyny among young South Korean men (as seen through the rise of a men’s alt-right movement on platforms such as Ilbe)22 to the way female K-pop idols are expected to perform for the male gaze.23 The military regime is not isolated. Rather, it is a vessel through which ideas regarding gender, sexuality, and nationalism percolate into broader society.

I implore anyone who is to some extent invested in Korea, whether you are a second generation Korean American attempting to grasp more of your homeland’s history or an avid K-pop fan, to do more than just consume the culture—the BTS, the k-dramas, the skincare routines—and find ways to critically engage with and ask questions about issues like Jin’s military service. After all, the history of militarism on the Korean peninsula is one that implicates over twenty other nations24—and by extension, those who call these places home. This piece is far from a complete overview. We direct you to the following sources and perspectives to learn more about the draft, its history, and its implications:

- Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea, Seungsook Moon

- The Origins of the Korean War: Liberation and the emergence of separate regimes, 1945-1947, Bruce Cumings

- The Unforgiven (independent film, 2005)

- D.P. (TV series, 2021)

- https://time.com/6265842/south-korea-birth-rate-military-service-exemption/ ↩

- Yezi Yeo, “The Good, the Bad, and the Forgiven: The Media Spectacle of South Korean Male Celebrities’ Compulsory Military Service,” Media, War & Conflict 10, no. 3 (2017): 295. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26392782. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Seungsook Moon, “Trouble with Conscription, Entertaining Soldiers: Popular Culture and the Politics of Militarized Masculinity in South Korea,” Men and Masculinities 8, no. 1 (2005): 72. https://doi-org.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/10.1177/1097184X04268800 ↩

- https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/03/13/national/socialAffairs/korea-military-military-service/20230313193813729.html ↩

- https://twitter.com/BIGHIT_MUSIC/status/1581905317545533440?s=20 ↩

- https://twitter.com/nodutdol/status/1602698541922750465?s=20 ↩

- Seungsook Moon, Militarized Modernity and Gendered Citizenship in South Korea (Durham: Duke, 2005), 48. ↩

- Moon, Militarized Modernity, 51. ↩

- https://www.statista.com/chart/29057/length-of-mens-compulsory-military-service/ ↩

- https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/08/21/why-doesn-t-south-korea-have-full-control-over-its-military-pub-79702 ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/17/world/asia/south-korea-conscription.html ↩

- Moon, “Trouble with Conscription,” 74. ↩

- Ibid., 73-74. ↩

- Yeo Yezi, “The Good, the Bad, and the Forgiven,” 293. ↩

- Ibid., 301. ↩

- Moon, “Trouble with Conscription,” 67. ↩

- Ibid., 72. ↩

- https://restofworld.org/2021/the-most-dangerous-weapon-in-south-koreas-military-is-a-smartphone/, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58660760 ↩

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/mar/04/south-koreas-first-transgender-soldier-found-dead ↩

- https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/home-28000-us-troops-skorea-unlikely-avoid-taiwan-conflict-2022-09-26/ ↩

- https://www.mic.com/articles/184477/inside-ilbe-how-south-koreas-angry-young-men-formed-a-powerful-new-alt-right-movement ↩

- https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2012/01/whats-behind-the-video-of-korean-soldiers-freak-out-over-girl-group/251212/ ↩

- https://www.unc.mil/History/1950-1953-Korean-War-Active-Conflict/#:~:text=During%20the%20Korean%20War%20and,under%20the%20United%20Nations%20flag. ↩